An important aspect of energy management is the measurement and verification (M&V) of energy management initiatives, whether behavior/operational or hardware/retrofits. Besides the obvious need to verify savings when the contract is based on performance, M&V also provides valuable feedback to participants and senior management.

But M&V waters can become muddied when on-site renewables such as PV solar and wind turbines are involved.

For instance:

- What is the proper accounting and valuation for the reduction of a kWh in a renewable-augmented building?

- Does one avoided kWh save zero dollars because a renewable kWh is “free?

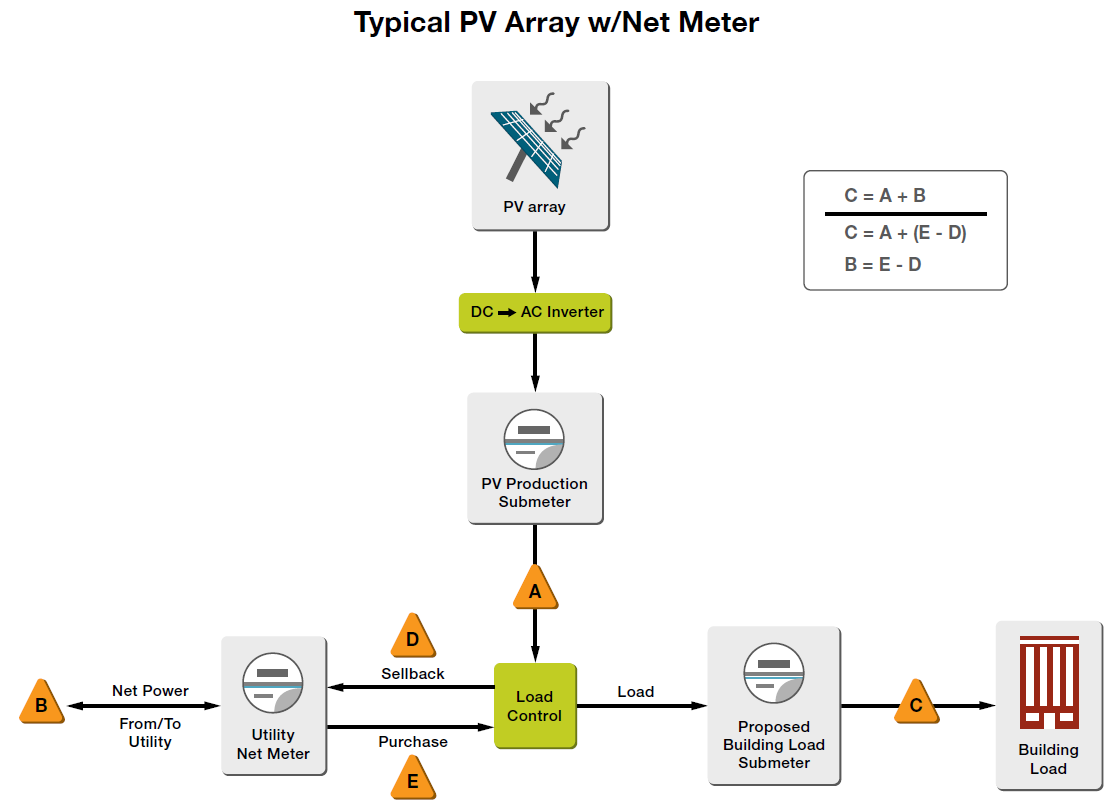

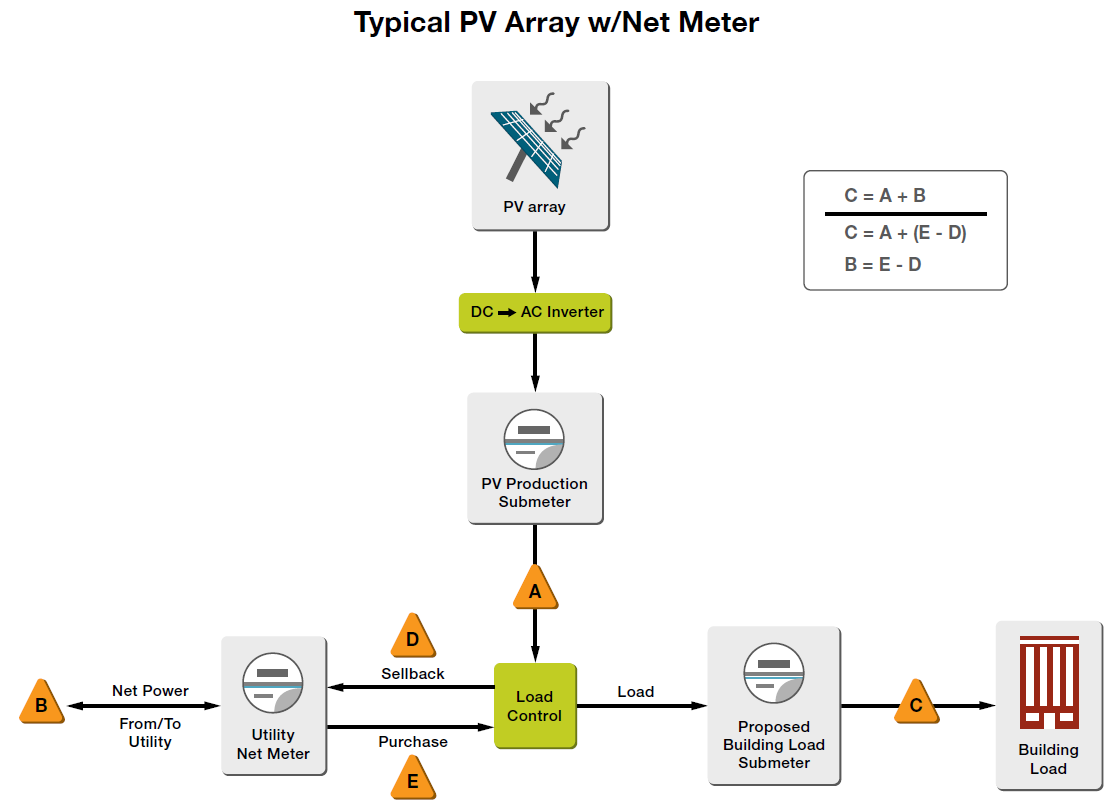

Here is a graphic illustrating a typical PV solar installation.

The building load “C” is met by a combination of solar (“A”) and grid (“E”) supplied kWh. Also illustrated is the common scenario of NEM – Net Energy Metering.

Because a solar array cannot be readily “throttled” at times of high production and low demand (for example, a sunny Sunday afternoon at a high school), state public utility commissions often require that the local utility buy back unused kWh (“D”) in an arrangement called Net Energy Metering. In essence, the meter turns backwards during periods of buy-back, reducing the net purchase of grid electricity (“B”) during the billing period.

One of the challenges of energy management in a NEM building is often the lack of a submeter on the building load (“C”). Prior to NEM, the main electric meter (“E”) provided a complete picture of the building load, giving the energy manager a valuable tool to monitor electricity usage.

With the addition of net metering, the utility company’s data must be analyzed in conjunction with the submeter on the renewable system (“A”) to yield the actual building usage at any moment, frustrating the efforts of many energy managers who have resorted to installing expensive building load submeters.

When energy management causes a one kWh of usage to be avoided in the building load, what’s the value of that kWh?

The building load control system first feeds all of the solar kWh the building can use, obviously up to the limit of the solar output, before it taps the grid. So in a period of zero grid use, avoiding the use of one kWh causes one solar kWh to be sold back to the grid. At first glance this may seem like a great deal – you’re making money!

But if you’ve entered into a long-term Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with a company that finances, installs and owns the system, you may have paid twenty cents for that kWh and the sellback rate (which does not typically include demand fees and other pricing components) may be less than five cents, which is not a good deal. In fact, oversized solar arrays are usually a very bad investment. The accounting is complicated by the fact that NEM often looks at the entire billing period as a whole, not at the day and time of each individual kWh buy-back.

If the building is using only grid or both solar and grid, then reducing one kWh saves one grid kWh and potentially an associated expensive demand charge.

The scenario can be even more complicated when grid kWh are supplied by a third party deregulated electric supplier that has yet another rate schedule. And don’t forget about ENERGY STAR and carbon footprint reporting. Proper reporting requires careful tracking of each kWh source.

We have identified four distinct scenarios and provide detailed instructions on which procedures to use in each case if you are using EnergyCAP software for utility bill management. Below are links to the best practices document for four different PV scenarios:

Scenario #1: Net metering by the LDC, without deregulated electric generation Supplier, owned system (no PPA).

Scenario #2: Net metering by the LDC, with deregulated electric generation Supplier, owned system (no PPA).

Scenario #3: Net metering by the LDC, with deregulated electric generation Supplier, PPA (non-owned system)

Scenario #4: Net metering by the LDC, without deregulated electric generation Supplier, PPA (non-owned system)

As you can see, the complexity of energy tracking and M&V reporting can be greatly compounded by an on-site renewable resource. That’s why a robust tracking tool like EnergyCAP is a good corporate investment strategy for a positive energy future.

{{cta(‘204f1f19-6c80-4b9b-8eac-39c72f31d051’)}}

Best-in-class portfolio-level energy and utility bill data management and reporting.

Best-in-class portfolio-level energy and utility bill data management and reporting.

Real-time energy and sustainability analytics for high-performance, net-zero buildings.

Real-time energy and sustainability analytics for high-performance, net-zero buildings.

A holistic view of financial-grade scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon emissions data across your entire business.

A holistic view of financial-grade scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon emissions data across your entire business.

Energy and sustainability benchmarking compliance software designed for utilities.

Energy and sustainability benchmarking compliance software designed for utilities.